As a non-native English speaker, over the years I’ve encountered moments of embarrassment and underconfidence for not getting a spelling right…or the pronunciation, sometimes the tense or sometimes the accent.

This has been the case for non-native speakers worldwide, especially in countries where English serves as an official language. Tsedal Neeley, a Harvard Business Administration professor quoted a FrenchCo employee in her Business Review, who was forced by their company to adapt to English communications, stating that the most “difficult thing is to have to admit that one’s value as an English speaker overshadows one’s real value.” Society has long emphasized the importance of mastering English, but today, I urge you to cast aside these notions and butcher the English language unapologetically, at least a little. Keep reading to find out why!

In 2023, around 1.5 billion people speak English either natively or as a second language, making it the world’s largest spoken language, followed by Mandarin Chinese (Statista Research Department). India is the largest country with non-native speakers of English measuring approximately 265 million (English Language Statistics), and we all know the culprit to be Colonization. However, rejecting colonial linguistic norms is one of the most prominent examples of deliberate anti-colonial and radical reformist behaviour that does more harm to the country than good, because using the language in question, which is now the lingua franca, has become essential to surviving in the increasingly globalized world. So, how do we strike a balance between continuing to employ our former colonizer's language and breaking free from cultural hegemony, while simultaneously celebrating our own linguistic identity?

The answer is Chutnification.

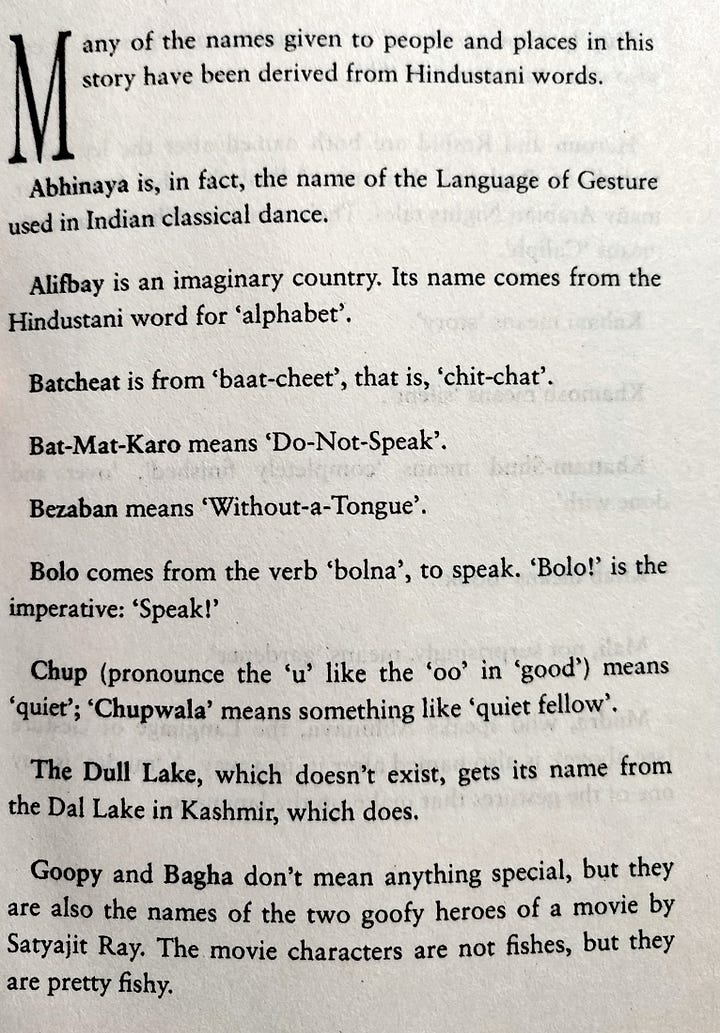

Chutnification was coined by Salman Rushdie in his Booker of Bookers, Midnight’s Children, 1981. It means the infusion of Indian elements into the English language or culture to create a new hybrid. The novel, known for its exceptional language use and blending of fact and fiction, history and story, and reality and sur-reality, mirrors the process of Chutnification. Just as Indian chutney enhances the flavour of a meal's main entrée, Chutnification aims to make English tangy, flavorful, and uniquely Indian.

“When ‘Midnight’s Children’ came out, people in the West tended to respond to the fantasy elements in the novel, to praise it in those terms. In India, people read it like a history book.”

— Salman Rushdie

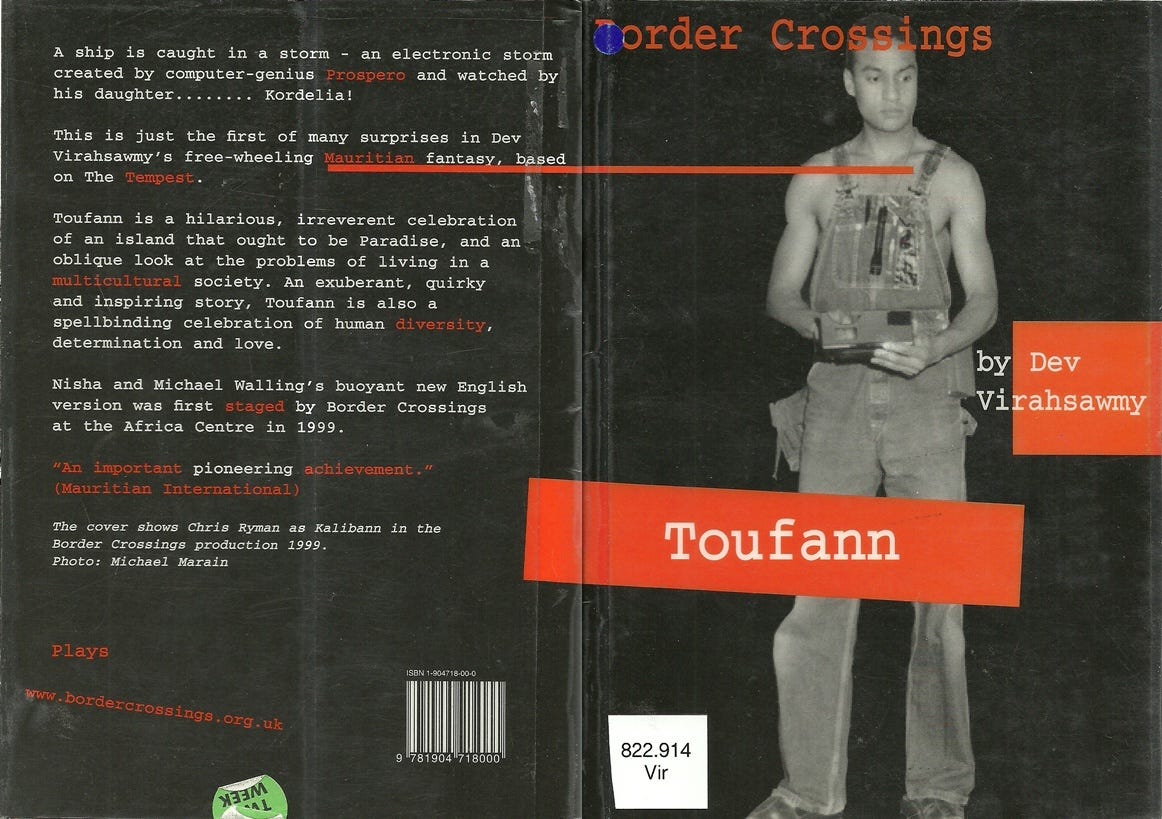

However, Midnight’s Children is not the first novel to employ Chutnification. Post-colonial writers and artists all over the world increasingly employ the hybridization technique. For instance, Khaled Hosseini normalizes the use of Farsi and Pashto words amidst English dialogues and description in his novel, The Thousand Splendid Suns; Chinua Achebe’s seminal trilogy, Things Fall Apart, No Longer at Ease, Arrow of God, as well as Ngugi wa Thiong’o’s Petals of Blood, present a beautiful Africanization of the English language, and were written long before Rushdie’s novel; Dev Virahsawmy’s Toufann is a remarkable Creolization of Shakepeare’s The Tempest.

“Shakespeare, like Hamlet’s father, haunts the postcolonial consciousness” (Pratyusha). The colonizers saw him as “an instrument of control and Christianity” and the colonized “made (him) their own.” Indian English writers rarely make the syllabus of NCERT or state schools’ English books in India, while Western authors and Shakespeare shape the young minds’ entire idea of English literature. The need for a revision of syllabi in schools to embrace stronger post-colonialist intervention becomes evident.

Most scholars argue that “Chutnification” is a modern-day synonym of words like Pidgin and Creole.

“Pidgin” is a special language with a very limited vocabulary and limited structures, used for purposes like trade by those people who have no common language between them. Some examples of pidgin are: (1) ‘I go go market’ (Cameroon pidgin) and ‘I chowchow’ for ‘I eat’ (Chinese pidgin).

“Creole” is when a pidgin language comes to be used for a long period of time by a community as a whole and forms its own vocabulary and structures. It is the product of two different languages originally used by the speakers (Rajpal). While I think chutnefied Indian English languages can be called Pidgins, they’re still a long way from being called Creoles, but the hybridization of Rushdie and his contemporaries is unfailingly paving the way for our own Indian Creoles.

The problem with “Indian” English

The term “Indian English” faces two major challenges:

First, India's linguistic diversity with 22 official and approximately 1400 unofficial languages makes it difficult to pinpoint a specific Chutnification model. In addition, Pidgin is something that happens naturally, like a survival instinct and cannot be forced. Second, the representation of Indian English on a global scale is primarily limited to “Hinglish” (a portmanteau of Hindi and English), neglecting other regional hybrids like Minglish (Marathi and English), Manglish (Malayalam and English), Kanglish (Kannada and English), Tenglish (Telugu and English), and Tanglish or Tamglish (Tamil and English) that exist in South India. This imbalance calls for a conscious effort to embrace and appreciate all forms of Chutnification.

Rushdie’s personal style of Chutnification is also limited to Hinglish, with the occasional blend of Urdu, making use of it as a “Pan-Indian” language instead of just a regional language. Hinglish is being increasingly preferred by the urban and semi-urban educated Indian youth, as well as the Indian diaspora abroad. It is also supported by numerous websites and Google voice commands.

Popular music, a central part of popular culture has also been a fertile ground for the “chutnification” of languages:

Talking about Bollywood and the Cassette culture in his research paper, “Popular Indian Culture: ‘Chutnification’ of Languages”, Rajpal, a Professor in Rajasthan University took the example of the movie “Shree 4204” which is well-known for the song- “mera juta hai japani, ye patloon Englishtani, ser pe lal topi russi phir bhi dil hai Hindustani’. The ‘linguistic hybridity in the word ‘Englistani’” in this song “bespeaks volumes of the truth about hybridized Indian culture” (Rajpal).

There are countless novels and books written in Hinglish, there are lecturers in the most renowned Indian Universities sharing discourses in Hinglish, and Bollywood is seen as one of the signposts of India by the West. But what about other languages and cultures?

This linguistic asymmetry can be better understood with Raymond Williams’ three types of cultures introduced in a section of his book, Marxism and Literature. Each culture's foundation is its ideology, which is comprised of the beliefs and practices that define its way of life. Williams provides a thorough account of how the three processes—dominant, residual, and emergent—make up the continuous system that these ideologies are a part of.

The term “dominant” describes the culture and ideology that the majority of people in a certain society hold (in our linguistic context, the application of Hinglish). Within the dominant culture are “residual” elements, a previous network of practices fusing into a new setting that can be found in the prevailing culture as relics from a bygone era (the residual element here, is the lingering belief that pure English speakers are culturally superior). “Emergent” refers to innovative practices that challenge the dominant culture (the emergence of other macaronic hybrids like Tenglish, Minglish, etc.) This contradiction is what sparks revolution and transformation. Ideologies that are dominant, residual, or emerging all help to shape culture. Therefore, there’s no linear or simple way to restore one's national identity following colonization, especially in a multicultural, multilingual state like India.

Those of us who use Hinglish do so despite our ambivalence toward it, or perhaps because of it, or perhaps because we can see in that linguistic conflict a reflection of other conflicts occurring in the real world, such as conflicts between the cultures inside of us and the influences shaping our communities. “Taking over English could be the final step in making ourselves free,” says Rushdie.

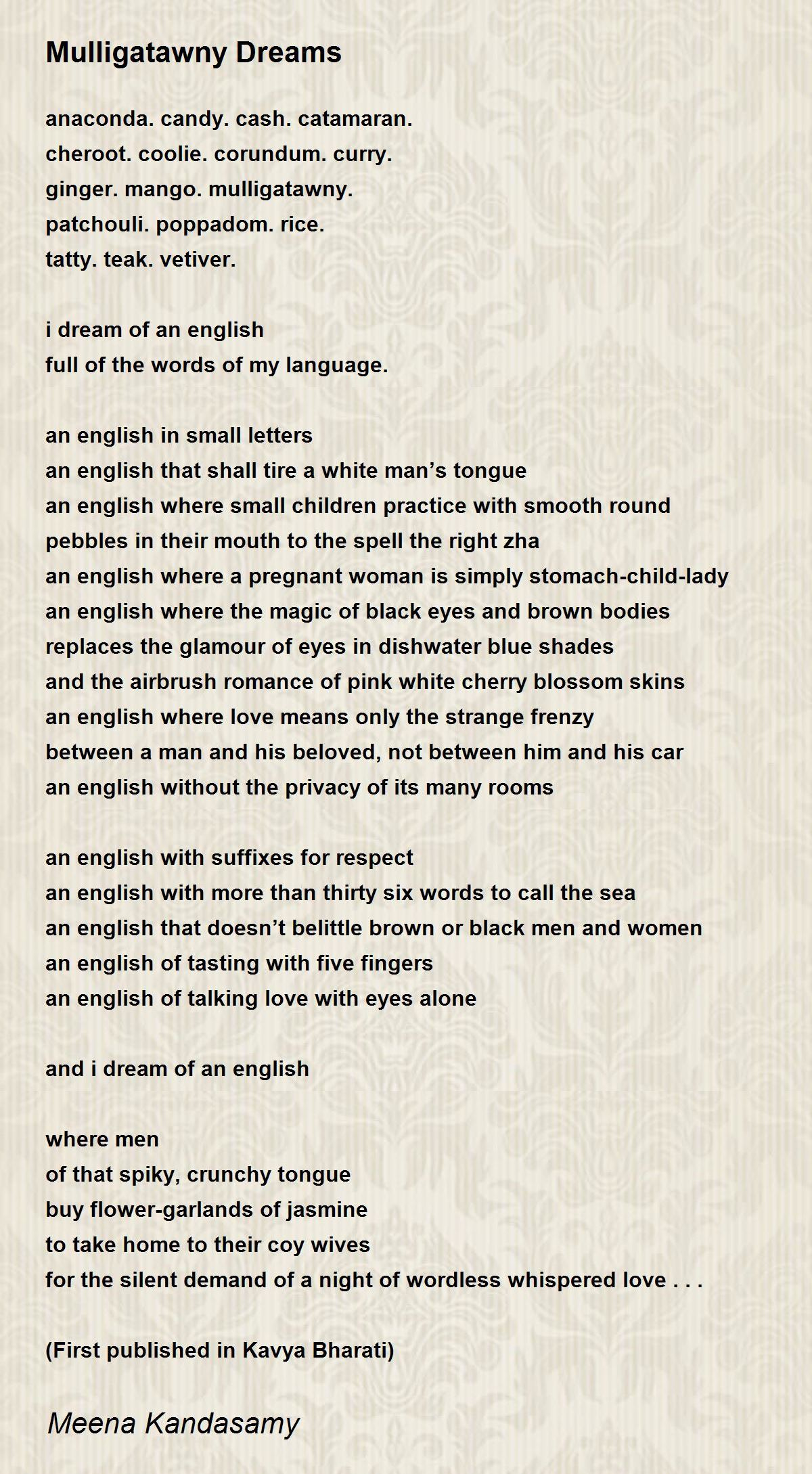

Meena Kandasamy, an Indian poet, fiction writer, translator and Dalit rights activist from Chennai, Tamil Nadu expressed the hope of having an English of her own(Tamglish/Tanglish) in her famous poem, “Mulligatawny Dreams”:

Meena’s writing intentionally subverts the conventions of the English language; she frequently omits punctuation, uses Tamil vocabulary without a footnote or an appendix, makes references to other cultures, etc. Similar to how the rest of the world, and especially Indians, have been taught throughout the centuries to understand British cultural references and history while eschewing our own, all of these deliberate actions make a statement beckoning the reader to research and put the effort to learn and comprehend the poetry and its references.

India also has some brilliant post-structuralists and post-colonialists including Gayatri Spivak who is noted for her personal brand of deconstructive criticism, which she called “interventionist”, and her concept of the subaltern; Homi K. Bhabha who theorized the concept of hybridity; Amitav Gosh, known for his stream-of-consciousness narrative strategies probing the nature of national and personal identity; Nissim Ezekiel, a foundational figure in postcolonial India's literary history and Indian Poetry in English; Nirad C. Chaudhari who wrote The Autobiography of an Unknown India and more. Yet, a huge set of the Indian population’s only impression of Indian Writing in English is popular fiction. Many of us might have heard of Salman Rushdie but only a few of us of the scholars I mentioned above.

Talking about the superiority of Indian English writing over regional or vernacular writing, Rushdie made a statement that created a lot of resentment among many Indian writers:

"the ironic proposition that India's best writing since independence may have been done in the language of the departed imperialists is simply too much for some folks to bear."

Amit Chaudhuri questioned:

"Can it be true that Indian writing, that endlessly rich, complex and problematic entity, is to be represented by a handful of writers who write in English, who live in England or America and whom one might have met at a party?"

According to Chaudhuri, IWE (Indian Writing in English), started applying magical realism, bagginess, non-linear narrative, and hybrid language to support themes that were viewed as microcosms of India and were purportedly reflective of Indian situations following Rushdie. He compares this to the writings of previous authors like Narayan, where pure English is used but cultural familiarity is required to understand the content. Additionally, he believes that the concept of Indianness is unique to IWE and does not manifest itself in vernacular writing. He further adds:

"the post-colonial novel becomes a trope for an ideal hybridity by which the West celebrates not so much Indianness, whatever that infinitely complex thing is, but its own historical quest, its reinterpretation of itself".

Hence, the crucial question now is not just whether to chutnefy or not chutney your English, which is already inevitably happening. The crucial question is figuring out what’s the right way to chutnefy it. Writers like Amitav Gosh and Salman Rushdie did employ a hybrid language but is their work more ‘Indian’ than the work of writers like R.K Narayan or Sudha Murthy who write in pure English but deliver the Indian culture flawlessly? This is something to think about.

Instead of obsessively translating regional words into "correct" English, we should let Chutnification flourish as a unique and distinct linguistic expression of our cultural diversity. While English remains essential for global communication, Chutnification enables us to reclaim ownership of the language, break free from insecurities related to English proficiency, and challenge the remnants of colonial mentality.

This brings me to the last concern in this casual discourse:

Professional adoption of Chutnification

Currently, the creative and art industries enthusiastically embrace Chutnification, as seen in Bollywood films, advertisements, literary works, pop culture etc. However, the question of whether Chutnification will be suitable for professional or business communications remains uncertain.

Chutnification is amiably provocative in the ways in which it’s being employed by these domains: in film—movies with characters speaking Hinglish or other hybrids,— titles like English Vinglish, Jab We Met, Life Anubhavinchu Raja, OK Kanmani, etc., in product advertisements, Pepsi’s tag lines ‘Youngistaan’, ‘Yehi hai right choice baby’, etc. However, it’s difficult to determine whether corporate settings would get accustomed to Chutnification, especially multinational or multiregional enterprises which could have to cater to larger, more diverse populations with many macaronic languages. Though colloquial chutnification is instinctively used in project meetings or group discussions, it’s still greatly frowned upon to make use of it in emails or official documents. We can only hope things will progress and Chutnification will break through all normative behaviours, bringing us closer to reclaiming our unique linguistic identities.

Why you should Chutnefy your English

Recapitulating this exposition, here’s some incentive for you to consider chutnefying your English:

Chutnification offers a powerful means to challenge the cultural hegemony associated with English and to reclaim your linguistic identity. By embracing Chutnification in all its forms, you can celebrate your diverse cultural heritage and promote an inclusive linguistic landscape. As we progress, it is essential to strike a balance between Chutnification and pure English, respecting both for their unique contributions to our nation's narrative. By encouraging the natural evolution of Chutnification and supporting its presence in various fields, we can move closer to a linguistically empowered future, free from the shadows of colonialism. As Salman Rushdie once proclaimed, let us savour the "pickling of time" and allow Chutnification to enrich our language and our lives!

“Symbolic value of the pickling process: all the six hundred million eggs which gave birth to the population of India could fit inside a single, standard-sized pickle jar; six hundred million spermatozoa could be lifted on a single spoon. Every pickle jar (you will forgive me if I become florid for a moment) contains, therefore, the most exalted of possibilities: the feasibility of the chutnification of history; the grand hope of the pickling of time!”

— Salman Rushdie

Thank you for making it to the end! I hope you’ll be reaching for your own pickle jars now :)

References:

Tsedal Neeley, “Global Business Speaks English”, Harvard Business Review, (May 2012): https://hbr.org/2012/05/global-business-speaks-english

Statista Research Department, “The most spoken languages worldwide in 2023”, Statista, (Jun 16, 2023): https://www.statista.com/statistics/266808/the-most-spoken-languages-worldwide/

Anil Yadav, “English Language Statistics”, Lemon Grand, (Jan 10, 2023): https://lemongrad.com/english-language-statistics/

Pratyusha Chakrabarti, “Shakespeare in India: On Stage and on Page”, Brown History, Substack, (Jul 20, 2023):

Rajpal, “Popular Indian Culture: ‘Chutnification’ of Languages”, Communication Today, (Dec 30, 2015): https://communicationtoday.net/2015/12/30/popular-indian-culture-chutnification-of-languages/

Raymond Williams, “8. Dominant, Residual, and Emergent”, Marxism and Literature, (1977): https://blogs.commons.georgetown.edu/engl-594-fall2013/files/2013/08/Marxism-and-Literature_Dominant_Residual_Emergent.pdf

Thanks for introducing this concept to us! It inspired me to look more deeper within, instead of looking all over the world.