Time Hopping with Jeanette Winterson: Chapter of the Present

Personal essay

I was sixteen when I had run away from home; so was Jeanette Winterson. Difference is that she never came back, and I did that very evening.

Of course, I know that isn’t the only difference. She is a 1959 Manchester-working-class-born, British queer writer. I am a 2002 Telugu-middle-class-born South-Indian queer literature student. It is not in history but in literature that our beings overlap. In her words I recognized a suffering with comforting familiarity and a resistance with familiar monstrosity. It is there in the pauses between her words that mine united. It is by reading what she doesn’t say that I learned to call her my friend.

Jeanette was a smarter sixteen-year-old than I was. She knew what she wanted to run from and what she wanted to run to. She could distinguish between a home and a house. She was reading English Literature A-Z at the Accrington Public Library. She found Austen, Eliot, Hardy, Dickens, and she understood Nabakov enough to disapprove. Even when trapped in a coal hole, her mind had never once stopped belonging to her. She didn’t associate with Stockholm syndrome; didn’t internalise the dialogue of her captor.

Or perhaps she did, and that’s what her pauses hide.

I left at five in the morning in a cab. I hadn’t yet known what incognito was, how to delete my search history or that if you book an uber from your uncle’s account, he could track you. It was a sloppy escape. It had all fear and no skill.

With the girls at school, I had been netflix-ing Thirteen Reasons Why and Pretty Little Liars but passed on Sherlock and Mindhunter, so I knew to cut my hair and change my clothes before I left but not how to erase my trail. Google gave away what I’d researched the night before – the directions to Hippie Island, Hampi from Inorbit Mall, Hyderabad by walk, by bus, and by car. I had the screenshots of the maps on my phone. I vowed to myself to never turn on the internet once I was out of the apartment and to discard the sim card eventually.

I’d stolen my uncle’s travel rucksack and stuffed it. Two pairs of Jeans, t-shirts, underwear, a towel, a bedsheet, water, charger, fruits, a small bag of chocos, cornflakes, any storable food I could find in the kitchen, twenty books, and an Oxford pair of dictionary and thesaurus.

The books slowed me down.

I organised them to fall flat on my back when I’m wearing the bag. It was softer like that, but the weight crushed me. I doubted if I’d be able to continue walking, but dropping the books meant having nothing to occupy my mind throughout the journey. And I was scared of my mind. It threatened to wreck me every time it was idle or bored. I needed their weight. With the escape they provided, I planned to ground it. Ironically, all the books I’ve read up to that point – coming-of-age escape fictions like Into the Wild and The Alchemist – were in favour of the opposite of grounding. They made me believe in madness and solitude. The feelings of claustrophobia and the marks of imagined chains on my skin heightened after these books,

boiled until there was no option left but to run.

I haven’t read many books in the early sixteen years of my life. The few that I read were all the wrong ones. Chetan Bhagat, Mark Manson, E.L. James and the most scandalous of all, Jagdish Vasudev. Inner Engineering – My uncle sold me this book on one of our early morning Yoga routines when I used to live with him.

‘Really sink your feet into the grass,’ he’d say ‘feel the texture of the rudraksha in your palms. Pray to the Sun.’

I did.

I believed the Earth was massaging my feet and that the early Sun’s only purpose was to smear soft strength into my cold dawn face. After we maintained this routine for a couple of months, I realised that I’ve been imagining a secret morning with nature all along, the one where I danced and giggled with the grass and the Sun, with no asanas to bind me to stillness. My hands swung like the branches of a tall wild tree and held no rudrakshas. This secret morning had no uncle.

Every year there would come a time when my uncle’s hatred for himself conquered him, and he would stop pretending that he was better than the rest of us. He’d take off to Isha Foundation – overgrown beard and loopy eyes – and come back a handful of sunsets later – new rudraksha maala around his neck, new oversized khadi kurta and new humming mantras that promised to ground him.

On one of these homecoming evenings, he wanted to spend time together and tried persuading me into staying up late to chat with him on the balcony. I had an exam at school the next day and barely studied. I planned to wake up early and sit with my books, which meant I had to have already been in bed. He looked at me, then at the half-moon in the sky and said,

‘You’re someone who’s always spending her present planning for the future– I’m someone who’s never come back from the past.

We’re made for each other.’

In her memoir Why Be Happy When You Could Be Normal, Jeanette Winterson wrote that there are two kinds of time: linear time which is also ‘cyclical because history repeats itself, even as it seems to progress’ and real or total time which is not ‘subject to the clock or the calendar and is where the soul used to live’. Linear time often exists outside of you. Inside you, chronology has no meaning, and the past is not fixed. We can return to the past, ‘pick up what we dropped…mend what others broke…(and) talk with the dead.’

For years, I’ve tried to shapeshift and insert myself into the pipes and drains of linear time, as if the only destiny is the gravity of The End; but I rarely ever fit and the times that I did, I kept getting lost in the gutter.

Two months ago, I’d been in an accident that brought a titanium rod into my leg. My mother still tears up every time she looks at the scars.

‘You have something foreign and artificial inside you now. It’s never going to return to its natural state.’

Contrary to what she thought, my leg did not feel different.

It felt broken, not different.

Certainly not artificial or unnatural. The doctors who operated on me reassured her it would be a minimal-scarring procedure. I’m a woman after all, and I must not like blemished legs. My mother thanked them.

We later found out that I have a genetic condition called Keloid scarring, caused by excessive collagen production in the hair follicles. I was going to have dark, raised, unpleasant looking scars, but not any critical side effects. Mother enquired about possible solutions – garlic, aloe vera, laser – discovered no permanent ones.

Her friends who visited me shared the same fears. ‘It’s never going to be the same. Mind the scars.’

I didn’t care much for ‘same’. I didn’t always like change either. But difference—difference challenges the entire ideas of ‘same’ and ‘change’. Jeanette knew this:

The wound is a sign of difference. Even Harry Potter has a scar.

She wrote an entire chapter on The Wound. No one knows paradoxes and plurality like adopted children do.

There is no one explanation that can fully capture the symbolic meaning of the wound. However, it appears that suffering is a sign or a component of being human. There is value here as well as misery.

What we notice in the stories is the nearness of the wound to the gift: the one who is wounded is marked out – literally and symbolically – by the wound.

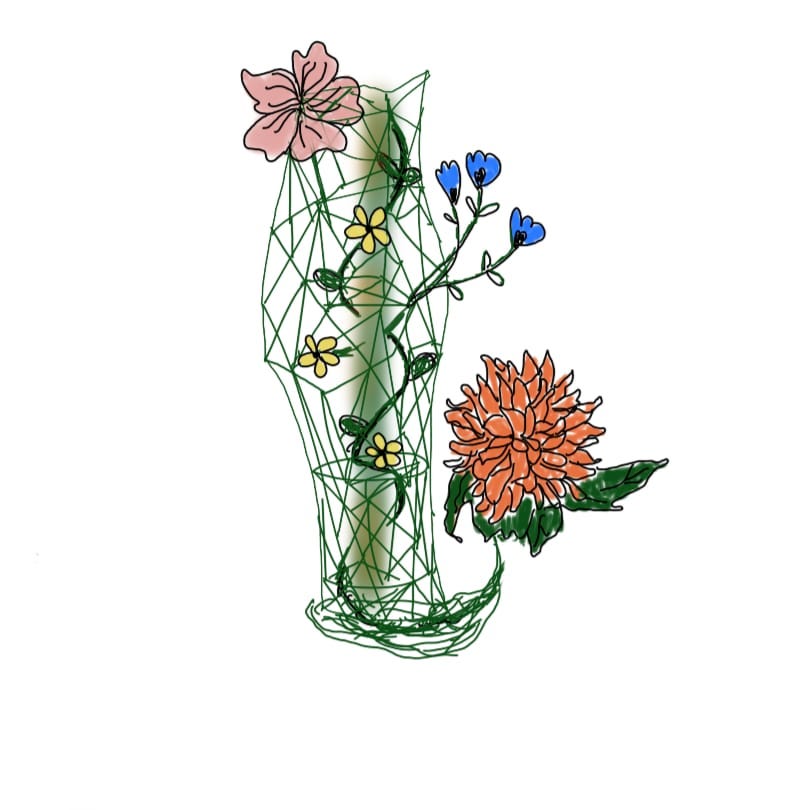

One of my friends named the rod in my leg titanium chan, or tit chan for short. They gifted me a drawing for this Bathukamma festival – chamanthis blooming out of the rod in a leg that’s wearing freakishly tiny elf-like shoes.

My mother’s bathukammas looked the same every year. First, a layer of lotus or pumpkin leaves. Next, a bed of thangedu, followed by gunugu, banthi, chamanthi and roses. The flower(s) on top however, could not be predicted. She created a mandala with whatever bloomed best in our garden that day. Every year, I look forward to the top layer. This year, tit chan bloomed the best.

I did not frequent real time like Jeanette did. I rarely stumbled upon it. My time was painfully linear for a long time. I’m constantly asked if it’s been difficult, if I must miss the leg of my past. I haven’t thought about it. As long as there is still pain in my leg, as long as I’m still hurting, I’m anchored to the present. Not unlike a pinch that brings a person back from their dream. Unless, the pinch is a steady throbbing, and it doesn’t allow you a window to wander into any dream.

I lived in this pinch till 2022, till I drew my uncle out of my life.

However, my pinch had a window. It was heavily curtained, but it was there. I caught glimpses through the gaps between the curtains every now and then. I was curious to see if the gaps would get bigger with time. When they didn’t, I wished for a gust to storm in and blow the curtains off.

Art and Literature are wild gusts. You must watch out for them whistling through the gaps in your window and door frames. You must focus obsessively on that sound till you find a way to unlock these windows and doors, and walk into the wind yourself.

After 2022,

when I was finally safe and wasn’t actively hurting, I fell out of linear time and into my insides.

I found a door, I walked out. But I wasn’t ready for the wind, it had no flooring. I fell. I was blown off.

I did not know wind. I did not know space. I did not know how to claim.

I knew walls, balconies and grass.

How do you navigate living in the real time?

A conversation with mom one night that started with sunsets and balconies led to her criticism of the modern dating scenario.

‘Will you go around and sleep with the entire city just to know what you’d like and not like in your life partner?’

I couldn’t tell if it was a comment or a question that anticipated an honest answer. I was useless in real time – I was bad at friendships; I often fell sick and rarely mustered the energy for connection. But I knew those who had the energy. I admired them.

‘If that’s what people want to do, they will. Why is that bothering you?’

‘Because it’s wrong.

You’re supposed to have a sacred bond with one person in your life. Not stain the sanctity of something so precious and spend the rest of your life ruined like that.’

‘But I’m not religious.’

‘It’s not about religion. It’s just wrong. Wrong. Wrong. Wrong.’

I’ve always known I’m not my mother’s ideal daughter. She would’ve preferred one who spoke sweeter and made her neighbours’ days, helped her cook and massaged her husband’s feet, liked going to temples and family functions, worked with medicine and married a male doctor, didn’t smoke or drink or like sex, went to the movies and parks on weekends, took her parents on vacations once a year and didn’t stay up late questioning the government.

She didn’t ask for a daughter of tragedies, like my dad once joked.

My uncle went to temples. He was closer to family faith than I ever could be. When you watched him close his eyes and mouth prayers in front of a lingam in the mandapam, you could tell it was not an act. Yet, he did not believe in God. ‘It’s the energies I’m here for,’ he’d clarify, ‘the architecture of a temple – the garbhagriha, shikhara and kalasha, the gaja stambham that grounds lightning, the cold stone or the white marble floor, the vibrations – all of it is spiritual science.’

I grew up listening to my uncle explain the world to me. He hated his life, he hated himself. But philosophy comforted him, like a personal lifeguard while paddling in the ocean. However, philosophy didn’t enter his insides. It always hovered over him, like a halo – separating him from the air on the other side.

He believed in prophets and that he might be one. He reasoned with loneliness as a consequence of prophetism, pain as the consequence of art, sex as the consequence of love and whiskey as the relief from it all.

‘Freedom is the most honest expression of love,’ he said to me once, and so he’d let me be free.

But before that, he made sure I knew a few things – consent laws vary across the world; most states of the west set the age of consent between fourteen and sixteen; and would I not turn sixteen this June? When he used to work in England, he saw many sixteen-year-olds dress and talk like adults. It’s a shame we were born in India; but Indians wed uncles and nieces all the time. Don’t they?

I left home with six hundred and sixty rupees in cash. Paid two hundred and thirty-two to the cab driver who wondered why a teenage girl was taking off to a mall – that doesn’t open until eleven – at five in the morning with a ridiculously heavy travel bag.

The mall was a safe place to sit and plan. The plan was to somehow make it to Hampi’s Hippie Island (this was in 2018, before it was shut down) and meet Mowgli, the manager of a cafe on the island and convince him to let me cook or paint or sing there in exchange for bed and food. Why Mowgli? Because the last time I went there, he seemed to like me and insisted I visit again. I did not have his contact number, the name or directions to the cafe but I believed I could make it. I was not a smart sixteen-year-old.

I say I left ‘home’, when it’s my uncle’s apartment that I left, because leaving there meant leaving my mother, father and little brother too – who stayed at home in Karimnagar, the one I’m writing from now – because they adored my forty-year-old bachelor uncle very much. I was sent to stay with him because Glendale Academy, the prestigious secondary high school in Hyderabad that I got into did not provide hostel facilities.

One small oddity disappearing from the family felt less catastrophic than turning everyone in it against each other. I believed the oddity was me.

I left a note. In beautiful cursive handwriting and humour. The family saw me as a weird one – with my abnormally large spectacles, weird books, weird songs that she was always humming, weird diary entries, all that writing on something called wattpad and all the alone time she spent on terraces. Jeevitha (the live-r), Mathimarupu (memory loss), Mahanati (great actress) were some nicknames for me. I joked about how relieving it would be for them to finally get rid of the burden of raising a weird one. I meant it. I assured them I’d be fine, that I’ll be back one day and that no one (parents or uncle) were to be blamed for my disappearance.

The day before I decided to run away, I had my first panic attack. It was the day of the Accountancy exam. I was not prepared. I tried studying but it did not work. I kept sweating, looking at the curtains, then zoning out. The balance sheets, the formulas, the boxes and the word ‘debt’ all over my fat textbooks haunted me.

My parents spent an immense amount of money to fund my study at Glendale Academy. I always thought of it as money I borrowed from them, a debt I might never be able to repay. I thought so because I did everything but study during my time at uncle’s; spent most days trying to act like a grown up in front of his friends. They came over to drink, cook, eat, play music, watch movies and debate complexities of the world. I wanted to learn wit and thought. I wanted to display wit and thought. I drank too, sometimes. I cooked for them and told the men they could cry when they struggled to. I believed I was the reason my uncle did what he did to me.

In December of 2021, I caught a fever that lasted twenty days, causing blood-diarrhea, vomiting and dizziness. My then boyfriend, Ajay, took me to the hospital and wanted to bring me back to his home and nurse me till I was better. But my mother wouldn’t have it. She forced me to stay at my uncle’s as it was the only place she could trust in Hyderabad. I told her everything about him once I got better. Then, uncle was forever out of my life.

Suddenly, there was nothing to fight.

All my body had ever known was fight, it did not know how to stop. So, it kept fighting wherever and whoever it could find. When if found no one, it fought me.

When I could climb stairs, I’d run up to the terrace after every dinner-table argument.

My terrace is painted in a bright beige colour. It has a water tank in the south-west corner wrapped in veins of various creepers, neighbour’s Guava tree arching from the north and Coconut and Hibiscus crowding the east right below the sunrise line. It has sparrows, hummingbirds, caterpillars and insects.

During the day, my terrace seems like a giant with a garden for hair. It sings until you share your troubles and your heartbeat steadies. You would return to the ground feeling light, like you’ve just taken a brisk walk on the clouds or like you’ve been playing in the arms of a colossal stuffed toy. At night, the terrace is the silent witches’ camp. You go up to be alone with the shadows prancing on the tank. They work their spells and you, yours. No looks, no questions asked – sharing silence like in a prayer or a reading room.

Every time I needed to but couldn’t climb to the terrace since the surgery, I ended up breaking things in the house. A pen – it started small – an AC remote, my favourite cup, an electric mouse.

Mother told me she’s afraid.

Most crimes are not planned, most crimes are swift, most crimes are anger.

Jeanette used to have an anger so big it filled up her house.

She said there is a part in many humans that is both ‘volatile and powerful’ at times – the towering rage that has the capacity to kill themselves and others, and threatens to overwhelm everything.

We needed to teach that ‘powerful but enraged’ side of us proper manners before we could engage in negotiation.

This ‘radioactive anger’ births a mass inside us. Jeanette called it the demented creature. This creature shouldn’t be fought or hated. It needed to be talked to.

The demented creature in me was a lost child. She was willing to be told a story. The grown-up me had to tell it to her.

I told her poems about female demons ripping out male tongues and feasting on them. They pleased her. I wrote about skull garlands weeping around raging necks, dark breasts bathing in pools of blood, long curls throning over lands they scorched, and satisfying echoes of screams in hell fire. I wrote the death of everything the creature desired over and over and over again, including myself.

...the creature loves a suicide. Death is part of the remit.

Death flashed me and disappeared swiftly during my accident.

When the anaesthetic wore off after the surgery, I remember thinking it’s the first time I experienced sleep that left no evidence. No dreams, no memory of tossing and tossing, no voices in the head. It was nothing. I wondered if that’s what death must feel like. Nothing. No evidence of movement.

Something about that stillness terrified me. I had to move.

Two months have passed, and I'm learning to walk again. The sooner I learn, the sooner I make a habit of movement. I am in a hurry. I’m counting steps and stairs, clacking the walking stick around the house and on the terrace. One to fifteen – fifteen to one – fifteen to thirty. I’m crunching, lifting, breathing. I’m training tit chan. I’m breathing. I’m straining. One to fifteen – fifteen to one.

Mom asks me to slow down. She’s talking, she’s yelling. I’m counting, I’m walking. She’s afraid. She’s yelling.

Why are you in such a hurry to leave home!

Because it is time.

Because you spent money you didn’t have on the surgery. Because you had to bathe, put on clothes and wipe the ass of a twenty-two-year-old. Not two, not sixteen; twenty-two. Because I break things. Because I do not know how to tame my creature. Because you’re afraid of me. Because I’m faithless. Because I’m a burden. Because I’m a daughter of tragedies.

She grabs my walking stick and steadies me.

She stares into my face, her left eye twitching like it does when she is about to say something she’s stubbornly certain of – the same way it did when I first told her about my uncle and she asked me if I wanted to go to the police.

‘You are my daughter! And I will NOT allow you to leave me.’

…

‘Okay,’ I set my walking stick aside and sit on the chair. ‘I won’t.’

She could’ve used any word, any word at all in the place of ‘daughter’ – sister, friend, neighbour, student, cat, dog, – doesn’t matter. All of them would’ve been true and all of them would mean only one thing –she is afraid of losing me. She needed me to stay.

And anyone who is needed cannot be a burden.

I have learned to read between the lines. I have learned to see behind the image.

My mom doesn’t have girlfriends; or boyfriends, or wild gusts of art and literature like I do. She has her family, and I am the only woman in it.

Perhaps I came back on the same day I ran away because I knew a mother who didn’t want her only daughter to leave her.

Perhaps I imagined her searching for me, and wondering like Jeanette did, ‘Why is the measure of love loss?’

I could not let it be loss.

It has taken me a long time to learn how to love – both the giving and the receiving. I have written about love obsessively, forensically, and I know/knew it as the highest value.

I think about the microsecond fall of the accident – the time between the crash and my contact with the floor. The strange chain of thoughts that held fast in the mind before it crashed and broke.

‘My parents would be disappointed.

I’ve caused them enough pain.

Another tragedy.

Would I live this out?

Do I want to?

It’s just a fall. Is it not?

What if I don’t?

Mom would be alone.

She likes chamanthi.

I like Chamanthi.

I want to–

I want to live.’

Inside the emergency ward – woozy from the painkillers, looking at other beds soaking with more blood than mine – I told my friend why I think I survived. He seemed to agree.

I must pick up what I dropped and mend what others broke.

I cannot let it be loss.

‘Chiron, the centaur, half-man, half-horse, is shot by a poisoned arrow tipped in the Hydra’s blood, and because he is immortal and cannot die, he must live forever in agony.

But he uses the pain of the wound to heal others.

The wound becomes its own slave.’ - Jeanette Winterson

Thank you Sammi, for reading and sharing your thoughts about it. You make it sound so wonderful! :) Made my day.

"My mom doesn’t have girlfriends; or boyfriends, or wild gusts of art and literature like I do. She has her family, and I am the only woman in it."

i had to stop and catch my breath multiple times and refrain from crying on the train in front of everyone.

i felt as if memory was being pressed into fine sheets and i was being folded into it, unable to tell which one was pressing into my skin - which one was the comfort i was being reminded of, which one was the fear.

I loved reading about your mother's bathukammas and your tit chan bathukamma